The artist, the activist and the developer: natural enemies or strategic relationships?

Timmah BallA large rectangular building appeared on the corner of Swanston and Collins Street. Its form mimicked London’s Turner Contemporary, a shed like structure elevated into cultural status symbol within the logic of contemporary architecture. As I passed the building on the tram, I asked a work colleague if it was a new train station being built as part of Metro Tunnel’s expansion of the city loop. It felt imposing enough, just as the vast holes that cut through the CBD as the project’s construction progressed, left an eeriness that unsettled the cities usual uniformity. A construction worker sitting opposite us interrupted, explaining that the infrastructure was part of the cross passage required for large tunnel boring machines that dug 40 metres beneath the earth’s surface. It’s exterior grace with metallic finishes hid this functionality. It was just a shed. And the relentless work undertaken by tunnel borers, the noise, the machinery, our capacity to dig beneath land in order to move faster above it was skewed.

Misinterpreting the building’s stately minimalism as an architecturally astute train station strangely aligned with Metro Tunnels broader strategic vision to utilise art and culture to hide the large-scale interruption which construction caused. Public art and installations were incorporated to reduce the perceived ugliness of machinery and building sites which would detract from the cities style and character. A designated unit called the Metro Tunnel Creative Program was established to ‘curate artworks and events to enhance Melbourne city life alongside the construction of the Metro Tunnel.’ The project goals outlined how delivering a ‘program of temporary creative works contributes to offsetting disruption around our worksites, ensuring Melbourne remains a vibrant and attractive destination as we build this city-shaping project’. Projects included pop up performances to coincide with festivals like Midsumma, to installations by leading First Nations artists during RISING. Permanent art works were also commissioned to embed the cities’ artistic identity within the transport system. Such projects included an art work spanning 5 underground stations by Yorta Yorta/Wamba Wamba/Mutti Mutti/Boonwurrung artist Marree Clark in partnership with the station architects Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners and consulting.

The Metro Tunnel Creative Program had value, it increased opportunities for artists whilst creating a built form imprint which decentred western colonial legacies through the vibrant work of Marree Clark. The creative strategy outlined how ‘the Metro Tunnel Project offers an exciting opportunity to strengthen Victoria’s creative sector by supporting connectivity between arts institutions, and investing in work that drives creative activity of artists, producers, educators, and the community.’ Furthermore, art was envisaged as a key community development tool which alongside civic infrastructure is a fundamental component to healthy and just communities. The overarching vision proclaimed that the program would generate:

A legacy of high quality experiences and places that put people first – contributing to Melbourne’s current and future liveability, international standing and reputation for creative excellence.

While arts practitioners often align their work with activism and social practice the Metro Tunnel Creative Program distorted this. Partly community oriented and connected to social outcomes it also remained strategically related to rapid development and government agendas which rarely ensure ‘liveability’ for all. Putting people first implies work that prioritises the right to place, where belonging isn’t determined by race, class and ability. But it seemed unlikely that the Metro Tunnel Creative Program intended to deliver this but instead remained stuck in the aesthetics of inclusion where place is enlivened with art rather uses and opportunities open to all. Like most funded arts programs within the nation state, it is rare to deliver projects or programming which aren’t partially aligned with government policies. Increasingly these partnerships include the private/commercial development sector which seeks public art to embellish creative appeal in a range of mixed-use and housing developments. And while this invigorates the public realm and supports artists financially there are complex negations required in these relationships which forces us to contemplate the role and value of our art practices both monetarily and morally.

These tensions stirred when I was asked to contribute to a Metro Tunnel project in partnership with Melbourne Writers Festival. Commissioned through the festival I was provided with the following details:

MWF would like to invite you to contribute a piece of fiction or non-fiction towards a publishing project sponsored by Metro Tunnel with a public-facing outcome. We’re looking for pieces at least 1,000 words in length that reflect life in Melbourne.

I was offered $2,000 a substantial amount as a freelance writer. While the parameters outlined were restrictive in the wider context of inappropriate sponsorship within the arts sector – (i.e. Wilson Parking, BHP, Woodside and others who fund major festivals) it didn’t seem completely unethical either. A government corporation increasing public transport seemed less culpable than other alliances even if their criteria limited arts role to incite debate and critique norms. I agreed to participate imagining that I could subtly draw in themes and issues that represented my values without breaking the agreed protocols. But I also questioned whether this marked an inevitable step towards coercion? A limiting of arts power to protest and draw attention to significant issues something which street and public artists played a major part in. Had the Metro Tunnel program effectively bought us out or was there a possibility to collude while maintaining an activist intent?

After submitting the piece, I received feedback that while the Metro Tunnel authority liked the overall concept there was one section that would need to be changed or removed. It referred to reparations and was the anchor point that drew my argument together. I had written the following:

Excavation commences on a new underground rail network which digs deeper into the city’s core than what was thought possible. It raises questions about how to approach Aboriginal Cultural Heritage and property procurement, as it is unclear if anyone can or does own the Earth’s core. For many, its depth implies that it is neutral territory, while others struggle to find clear recommendations in current planning legislation. There is growing uncertainty as to whether digging should continue or if property parcels should be purchased deep beneath the ground, as is protocol with the development and construction of other civic infrastructure. Tensions mount beyond property ownership as people debate how Aboriginal Cultural Heritage should be interpreted and whether this project could become a touchstone in Aboriginal architecture and design. Debates continue for almost a year before a landmark decision is reached. To appease all parties and ensure fairness it is decided that seventy-five percent of ticket revenue for use of the network will be transferred to Pay the Rent.

I wasn’t particularly surprised that a land-based government infrastructure project was concerned about publishing work that addressed strategies to compensate traditional custodians for the loss of their Country. Reliant on the commission and unwilling to engage in an argument that was impossible to resolve I chose to ameliorate the need to Pay the Rent by rephrasing the section to the following:

Excavation commences on a new underground rail network, which digs deeper into the Earth’s core than what was thought possible. It raises questions about the meaning of architecture in an expanding city. Engineers, borers and other technicians spend days beneath the ground creating a system to support this growth. Months and months of digging leave many disinterested in resurfacing. The vacuous openings created feel like portals into new worlds, which remain invisible to most people.

Bereft of the original politics I tried to imagine that this version suggested the beginnings of an alternate social order where government officials resettled in the tunnels freeing space on the surface for the land’s rightful custodians the Bunurong Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nation. But it was a stretch to imagine that this message translated with the same impact of the original. Public art in a development context created new opportunities for artists but arts role to agitate and question social injustices diminished. A strange irony evolved where partnering with the developer enlivened the city with art, but arts role to critique the direction the city moved in disappeared.

If the Metro Tunnel Creative Program is evident of the development sectors increased interest in art it also reveals that this relationship is bound to specific agendas or priorities. Art is used within new developments as quickly as it is destroyed in others if the context doesn’t fit the wider development goal. A significant mural is featured on the Kensington Community Recreation Centre, a short walk from the Kensington (Western Portal) – (another section of the Metro Tunnel featuring large scale public art). Like the major transport development, the community centre is also part of a $10.2 million “redevelopment” scheme and was demolished by the City of Melbourne in order to be build a new state of the art building. In doing so the community mural on the existing building’s entrance created by children from El Salvador in the early nineties was also be destroyed. If developers are incorporating public art, the goals remain vested in development and specific agendas rather than the social value of art, culture, heritage and histories. New murals are created within walking distance to a community recreation centre whose current mural will vanish. Because a state government agenda considers one worthy as the local council remains apathetic towards preserving the mural by Salvadoran children. As Dr. Tania Cañas elaborates in the article Constructing Absence: Enforced Temporariness in the Destruction of a Salvadoran Community Mural:

I had been calling local media, legal aid, and local arts organizations in hopes of garnering some attention about the mural’s importance and to demand accountability from the City of Melbourne in their decision to destroy this public artwork. After a Kafkaesque series of calls and emails in an attempt to make contact with the City of Melbourne, the council finally let me know the mural was “always meant to be temporary… a moment in time… an expression of its time”; “something that we cannot preserve.”

The council’s indifference highlights how certain cultural histories and art practices are not considered worthy while others are. The City of Melbourne lacked the investment or desire to elevate the Salvadoran mural yet The Metro Tunnel Creative Program consciously valorised certain aspects of Kensington as a method to generate new art in the same vicinity. Without doubt Metro Tunnel’s values are tethered to colonisation as if the contribution and presence of the Salvadoran community never existed and was never strategic enough to be saved. The Metro Tunnel strategy states that:

Kensington was established in 1856 after a Crown Grant was made to the Melbourne City Council for cattle saleyards and abattoirs. Aspects of the area’s layered history are represented in the heritage residential streetscapes and industrial buildings. Kensington today supports a diverse and vibrant community. A number of creative, cultural, social and sporting organisations cluster in and around the area. These include JJ Holland Park sporting clubs, and community and cultural organisations. The western portal emerges near South Kensington Station and connects to railway lines running west near the Maribyrnong River. North of the station sits a large sport and recreation precinct while housing abuts the station. To the west is an industrial zone. From the existing railway line the view is open as it looks out onto largely flat ground, backgrounded to the north by a rising slope and residential housing and flats.

This strategy and the creative outcomes that emerges from it further obliterates the presence and cultural contributions of Salvadoran communities forcibly displaced and resettled in this area. While the absence of pre-invasion Aboriginal livelihood and their continuing culture and communities also seems inevitable. Instead, the strategies conception of the area is rendered through a permeant art work incorporated into Kensington (Western Portal) which runs along South Kensington Station abutting JJ Holland Park. The artist Stephen Banham was commissioned to create a 300m long flood wall titled One Day in the Park. The Metro Tunnel website describes the work as community informed stating that it ‘explores the intimate and everyday stories of the local community within the park in a playful and imaginative way.’ It further outlines that:

Engagement activities with the Kensington community were undertaken by RIA, the contractor delivering the Metro Tunnel western tunnel entrance on behalf of Rail Projects Victoria (RPV), to help inform the design of the 300m flood wall at Childers Street.

In 2020, RIA and Stephen Banham engaged directly with the Kensington community for inspiration and ideas as Stephen further refined his design.

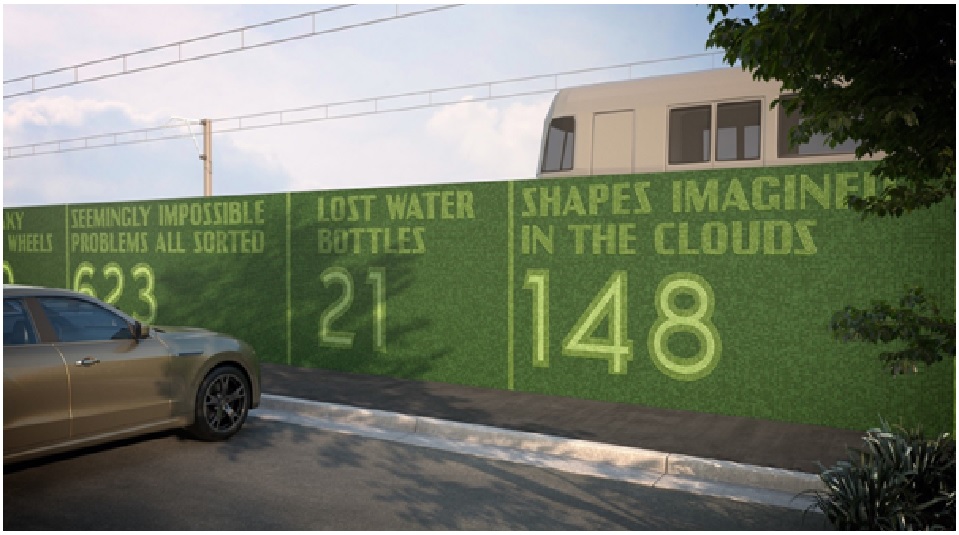

The bland uniformity of the mural evident in the artists impression below sharply contrasts the intricate details and luminescent beauty captured by the Salvadoran children in a mural that celebrates justice but was demolished The Metro Tunnel’s website reaffirms the narrative of Salvadoran invisibility illustrated in Banham’s work. The Kensington community were “engaged” to “inspire” the artist but the permeant art panelling 300m in length is only capable of capturing the stories of lost water bottles. The stories of BIPOC migrants and First Nations people are remiss.

Banham’s mural indicates a public art politic that is founded in white settler neutrality. One that assumes that the local community and park user are demographically white and middle class. This enables consultation to occur while the stories of racial minorities remain hidden in plain sight. The scale of the work becomes another loss, as we are left to imagine what could have been if others were consulted. If the mural by Salvadoran children was saved and reinstated within this new development, 300m in length that is able to commemorate the clumsily misplacement of water bottles but forgets the loss of life. Instead, a moment in history disappears and the art of development cements a culture of homogeneity.

References

Dr Tania Cañas, Constructing Absence: Enforced Temporariness in the Destruction of a Salvadoran Community Mural, The Avery Review 2021/2022

Metro Tunnel, Creative Strategy, https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/307668/MT-Creative-Strategy.pdf

Victoria’s Big Build, Legacy artwork, https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/projects/metro-tunnel/community/art/legacy-artwork

Victoria’s Big Build, Stephen Banham: One Day in Our Park, https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/projects/metro-tunnel/community/art/legacy-artwork/stephen-banham-one-day-in-our-park

Victoria’s Big Build, The Art of the Metro Tunnel, https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/projects/metro-tunnel/community/art

Victoria’s Big Build, Creative program, https://bigbuild.vic.gov.au/projects/metro-tunnel/community/art/creative-program

Timmah Ball is a nonfiction writer, researcher and creative practitioner of Ballardong Noongar heritage. In 2018 she co-created Wild Tongue Zine for Next Wave Festival with Azja Kulpinska which interrogated labor inequality in the arts industry. In 2016 she won the Westerly magazine Patricia Hackett Prize, and her writing has appeared in a range of anthologies and literary journals.