Constructing Absence: Enforced Temporariness in the Destruction of a Salvadoran Community Mural

Tania Cañas*republished from The Avery Review

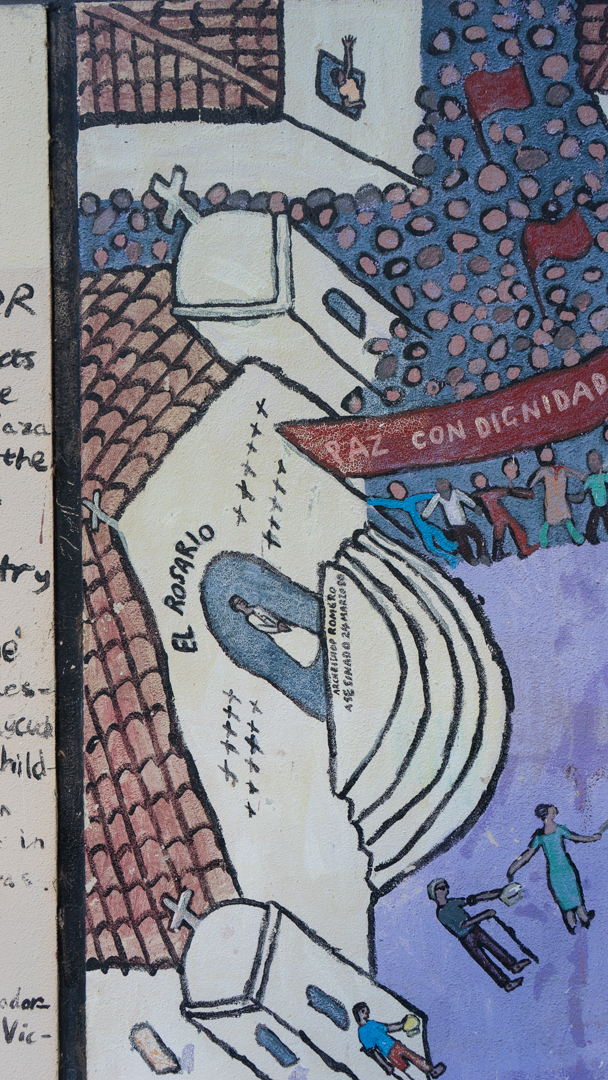

A Salvadoran community mural is set to be destroyed by the City of Melbourne Council as part of a $10.2 million “redevelopment” scheme in the gentrifying neighborhood of Kensington.1 Kensington, today, is a place where you can purchase ethically sourced Salvadoran single-origin coffee at a local café, and also a suburb demolishing one of the only public representations of the displaced Salvadoran community in Australia.2 The mural was painted on the exterior wall of the Kensington Community Recreation Center by artist Ben Laycock and a group of young Salvadorans from the housing flats across the road in 1990. It was a project of the Comunidad Salvadoreña Unificada en Australia (the United Salvadoran Community in Australia); the Kensington Community Center; and the Department of Youth, Sport, and Recreation. The mural depicts the Parque Libertad (Liberty Park) in San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador. A monument to justice sits at the center, a statue of the “angel of freedom,” who holds up two laurel wreaths at equal height to commemorate the primer grito de independencia (said to be the first cry for independence from the Spanish empire in Central America).3 There are families picnicking around it, people riding bicycles, a child aiming an ondia toward birds in a tree, a woman selling bebidas, a Don in a sombrero selling balloons, a man sitting on a bench feeding birds, an abuelita on a rocking chair, children playing marbles, aguacateros (street dogs) roaming the streets, and even a violin serenata. The park is surrounded by cafés and shoe and tortilla shops. In the top left, people are protesting arm-in-arm, holding banners that read “el pueblo unido jamás sera vencido/the people united shall never be defeated” and “paz y dignidad/peace and dignity.” Further down sits the church of El Rosario, which, as a site of refuge for early community organizers, draws attention to the role of liberation theology.4 At the church’s entrance stands the recently canonized Archbishop of El Salvador, Óscar Romero, who was assassinated in 1980 during mass. In the top right, a political prisoner raises their fist through the bars of a cell, saying “libertad o muerte/liberty or death.” Below him a suited bureaucrat exits a limo and enters the Palacio Nacional.

It was getting late for my scheduled afternoon call with the program manager of Art and Heritage Collections at the Melbourne Council. I emailed him a reminder, and he abruptly replied that he had been “directed [by senior management] not to proceed” and that I should instead expect a call from a team leader “at his convenience.”5

By this point, I had been calling local media, legal aid, and local arts organizations in hopes of garnering some attention about the mural’s importance and to demand accountability from the City of Melbourne in their decision to destroy this public artwork. After a Kafkaesque series of calls and emails in an attempt to make contact with the City of Melbourne, the council finally let me know the mural was “always meant to be temporary… a moment in time… an expression of its time”; “something that we cannot preserve.”6 This “we” felt like a kind of linguistic border management strategy, a way to note dichotomy and dominance rather than collectivity. This “we” positioned me as an outsider rather than a member of the Salvadoran displaced community, a community that did not have a say in the council’s decision to demolish the mural. Australia is home to the third-largest Salvadoran population outside of El Salvador, having arrived primarily through the Refugee and Special Humanitarian Program in the 1980s and early 1990s.7 As much as 92.6 percent of the Salvadoran-born population in Australia arrived before 2001.8 In the city council’s explanation I heard the enforced temporalities prescribed by the colonial project. Like the mural, the Salvadoran community was always meant to be temporary. For the “we” of the council, the mural asserted a presence, the enduring existence of a community that threatened the very idea of our perceived temporality. The mural, in this way, became a site to ask urgent questions: Who gets to be remembered and what gets to be preserved under settler colonialism? How does memory and embodied archiving occur for sites deemed to have no “heritage significance” by national and state-level heritage organizations?

These institutional practices of imposed temporality make up a form of “heritage regime”—what Tracy Ireland, Steve Brown, and John Schofield see as comprising a series of “rigid aesthetic and conservation paradigms, as well as identity and ownership claims and deeply invested national narratives.”9 These practices are not merely about who remembers or how remembering takes place but are an active process of “value creation and negation.”10 Colonial regimes and discourses seek to construct and enforce a temporality of communities, as either permanent or temporary. This enforced temporality is foundational to the very invention of Australia as a nation-state by claims of terra nullius and supports broader politics of erasure. As Patrick Wolfe notes in “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” settler colonialism relies on everyday acts of destruction and genocide: of peoples, places, histories, and ecologies.11 From the Stolen Generations12 to the refusal to acknowledge the Frontier Wars;13 from Aboriginal deaths in police custody14 to bulldozing the sacred Directions tree to make way for a highway.15 These are ongoing, everyday violent acts in so-called Australia that seek to construct non-white lives, bodies, communities, and cultural artifacts as disposable. The Directions tree was a culturally significant tree to the Djab Wurrung Nation yet it was deemed not of “heritage significance.” This incident highlighted very clearly that “cultural significance” and “heritage significance” are two positionalities and frameworks at odds with each other. Heritage practice seeks to imbue a permanency to certain sites and build the colonial narrative, whereby sites like the Djab Wurrung tree, which has stood for well over hundreds of years and since well before the British invasion, are deemed temporary—an obstruction to the building of the colonial permanence narrative. Claims of cultural significance question the very foundations of the nation-state, whereas heritage significance seeks to build a dominant and enduring narrative of the nation-state through everyday acts of erasure and elimination.

As Munanjahli and South Sea Islander professor Chelsea Watego asserts in Another Day in the Colony, “the world has only every imaged Indigenous peoples as destined to die out.”16 And yet, despite this protracted violence, First Nations liberation struggles assert “We are still here.” This existence is inseparable from the past or the future sought by colonial regimes, the European frameworks of land ownership, white subjecthood, and possession that are continually reinforced and constructed as permanent in the present,17 the $6.7 million replica of Captain Cook’s ship that first brought him to the Australian continent,18 the heavy policing of colonial monuments during the global monument movement,19 the geospatial border surveillance and management mechanisms that sought to build Australia as a white colony, including the white Australia policy20 and the earlier UK Assisted Passage Migration Scheme (1945). Temporary and permanent therefore relate to the destruction and construction of colonial narratives, politically laden hierarchal value judgments, mechanisms of daily border management, and cultural hegemony. In colonial Australia, certain communities are structurally, historically, politically, economically designed to be temporary, and simultaneously subjected to the violence of colonial practices of saving, protecting, archiving, and preserving. As Timmah Ball notes, “whites often think remembering is a plaque or a statue.”21 The durability of these materials as they impose upon the landscape are part of the strategy of building and assuring the permanence of colonial hegemony. Plaques and statues enforce not only narratives but ways to remember that are repetitive and performative, that direct acceptable forms of public remembering.

The displaced community is always considered transitory in the colonial project, a temporary problem to be “fixed” through nation-state mechanisms of management. That is, a community is temporary before members are “granted” citizenship, temporary before deportation, temporary before assimilation, temporary before being pushed out to peripheral suburbs by gentrification. In other words, displaced communities are temporary until subsumed and complacent within the legal, economic, and social conventions of a settler-colonial state. And yet settler colonialism ensures that this is continually deferred, that temporariness is a permanent reality, either through a lack of bridging courses and stable housing or an excess of daily monitoring. Assimilation is demanded yet statefulness is never experienced.22 This deferral, this feeling of permanent temporariness, is a tool of ongoing occupation and dispossession. It is forged through various mechanisms, through the division of communities upon arrival (assigned to different sites across the north, west, and southeast of Melbourne) and the destruction of housing flats and, now, as with the mural, of cultural, visual, and emplaced reminders of temporality, led by cultural and government institutions. As Beatriz Santos writes with regard to the Salvadoran community, in the context of Australia’s long history of migration restrictions and specific border policies, the expectation is “to assimilate into the mainstream society.”23 In the case of the Salvadorans arriving primarily in the 1980s, we were divided and assigned to refugee hostels and transit sites across Melbourne, such as the Enterprise Hostel (Springvale), Midway Hostel, Transit Flats (Maribyrnong), and housing commissions (Ascot Vale), as well as Kensington.24 In 1999 Kensington demolished one of its four high-rise flats, further displacing the already displaced Salvadoran community:

I thought about these displaced communities when the Melbourne City Council admitted that the mural “didn’t come up during the [redevelopment’s] consultation phase.”26 I thought about how these communities, through displacement, across and within national borders, are further removed, separated, cut off from the process. Of course the mural “didn’t come up during the redevelopment’s consultation phase” if the communities who care about it most, who the mural not only depicts and represents but who are also co-creators of the mural, are not actively considered and invited into the conversation. Not hearing these voices must not be conflated with a lack of interest; rather, it speaks to the council’s incapacity or unwillingness to account for the historical dynamics of how local communities change.

In Footscray, a suburb neighboring Kensington, the Vietnamese community recently lost the only existing bilingual Vietnamese program in Australia despite strong grassroots campaigning by parents, teachers, students, and allies.27 Communities do not just disappear; they are made to disappear—in a multitude of violent ways. Destruction is a “future assembling technique and project.”28 It assembles future publics and also denies future publics and assemblages. That is, colonial forces of destruction “create a reality they appear to describe.”29 They enact, through violence, certain realities over others. Destruction is therefore not only an act of construction but an active denial of a multitude of other futures, possibilities, and communities. It affects imagined and actual future publics, imagined and actual future sites and ways of being and being seen together, organizing together, gathering together.

I visited the site of the mural on several occasions in 2021 with fellow Salvadoran artists, both displaced and generationally displaced. The mural was a place to connect where we might not have done so. We gathered over fried yuca and stories. The mural now sits behind a wooden border and red and white tape.

Heritage Victoria says on its website that it “makes decisions about the most important historic heritage sites in Victoria.”30 It recommends places for the Victorian heritage register and Victorian heritage inventory, as well as regulates and enforces the Heritage Act 2017.31 According to Heritage Victoria, the mural does not have “state level heritage significance” status, thus not only is there unwillingness from the council, but the developers of the new complex have no official obligation to preserve it.32 The existing building displays another artwork, a painted steel sculpture titled Eels (2006) by Mothers Art Productions, on a wall within the public swimming area. This work was one of seventy-one pieces created for the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games and was later gifted to the center by the State Government of Victoria.33 Unlike the mural, this piece will be professionally saved, stored, and reinstated in the new complex. Despite Eels not being on the heritage register, it was, however, allocated resources for its preservation, thus adding to the production of its “value” in the local narrative. The mural is also not documented in the official City of Melbourne City Collections as, according to the official website, since 2005, “contemporary art has been a particular focus with acquisition advice generously provided by a panel of external art experts, who are part of the Collection Advisory Panel.”34 I wondered if that is what the council meant when they communicated to me that the mural “does not fit the criteria” for inclusion in the City Collections. The council reassured me that the advisory panel had vast international experience—as if that experience would justify their decision to destroy the mural, or as if the Salvadoran community had no comparable relevant knowledge, authority, or experience.

The very framework of the “contemporary” is tied to colonial logics and structures of power. It imposes a linear temporality upon people, practices, and sites, a forced dichotomy between “traditional” and “contemporary practices,” between the past and the future, between change and no change. As noted by Rasha Salti, “different ideologies invest the past, present and future each with their respective modes of valuation.”35 Ultimately what is worth “saving” is a question of who is worth remembering—and if that “who” conforms to the “we,” to the patriarchal, colonial, and capitalist order of the nationhood. The community mural in Kensington does not conform to neoliberal, neocolonial ideologies that favor individualism. Rather, the community mural was given a grant and was collectively painted and authored, the names visible at the bottom of the mural, now fading away. This is not a mural painted by an internationally endowed visiting artist such as Banksy or Roa. But the colonial narrative requires the propping up of the individual to attribute a singular “hero” as “founder,” “explorer,” and “pioneer,” names to be littered all over the urban landscape; from Hoddle Street, named after Robert Hoddle, the designer of Melbourne’s famous gridded system, likened to a “military formation” by First Nations writer Tony Birch36; to Deakin University, named after the former prime minister, Alfred Deakin, who in 1901 stated: “In another century the probability is that Australia will be a White Continent with not a black or even dark skin among its inhabitants”37; and to the Victorian state and Melbourne, named after Queen Victoria and Lord Melbourne, respectively.

There is another separate piece in the area of Kensington (about a ten- to fifteen-minute walk from the recreation center) called the Lynch Bridge Mosaic Mural.38 Created by Elizabeth McKinnon in 1992, the work was intended to mark the old Newmarket saleyards, “a place where livestock and money changed hands, a meeting place where city and country met, a workplace.”39 Over email, the head of Creative Urban Places of the City of Melbourne attested to the difference between the mural and the mosaic, claiming:

With regards to the Lynch’s Bridge mosaic (unlike the [Kensington] pool mural) it was formally commissioned and is in the collection. Note that [it] is made of the durable material that is mosaic, not paint. The El Salvador community is celebrated in one of ten panels.40

The mosaic piece predominantly depicts colonial Australia: farming imagery, cattle, and sheep dogs. It is about “pastoral industry” and “culture.” Yet the head of Creative Urban Places’ note suggests that the Salvadoran community should be happy that we are “celebrated” at all in the work, that this singular representation should be enough among the endless statues of colonial figures across Australia. The response also contradicts Victoria Heritage’s decision to classify the New York artist Keith Haring’s 1984 mural in Collingwood, Melbourne, as heritage due to “its historic, aesthetic, and social significance.”41 The piece was painted directly on a wall yet was restored and classified as a key consideration in the “sensitive” redevelopment of Collingwood Tech to the snazzy new arts precinct Collingwood Yards.42 Preserving it involved extensive research, technical investigation, retouching, cleaning, and repairs done directly to the mural.43 Furthermore, Melbourne prides itself on its internationally famous street art scene, with sites like Hosier Lane regularly making the top “must-see” or “to-do” lists of the city. 44 Its durability was never a question of material (i.e., paint versus mosaic) but of significance. As noted in “Situating (In)significance,” significance is not inherent but rather assigned, through an operationalized process of “values-based” heritage management.45 That is, significance is assigned according to how it can serve and maintain the heritage regime of settler colonial Australia.

In all my exchanges with the City of Melbourne what became particularly contentious was terminology; according to the council, their plan for the mural was redevelopment not destruction. As a narrative strategy, the term “community” is not exempt from being operationalized in particular ways that are ultimately exclusive and destructive. In this regard, destruction was incompatible with the term “redevelopment.” For the council, in building a community recreation center, the redevelopment couldn’t be destruction as it was supposedly building community. It was for the benefit and well-being of the community. However, this does not mean community spaces are exempt from actively contributing to gentrification. In the context of settler colonialism, community is often wielded in service of the discourse of the nation—rather than as a radical potentiality of alternative modes of relationality and organizing. In the case of Kensington, the neighborhood recently joined the “million dollar club,” a term denoted to Melbourne suburbs where the median house price has reached a million dollars. Alongside the building up of a “community” recreation center, the redevelopment project also marks which forms of community are denied their existence, evidenced by the destruction of the mural.

Created at a time when community murals were often pseudo-attempts at engagement that aligned with 1980s visions of community cultural development, multicultural policy, and economic rationalism—the Salvadoran mural is fiercely political and strikingly specific. The piece is joyous. This is particularly significant as the mural was painted before the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords that officially brought the civil war to an end in 1992. The mural does not rely on depicting refugees as victims, as symbols of an apoliticized helplessness. Rather, it depicts community, collective desire, defiance, and dignity. In this way the mural marks a kind of epistemological, ontological, and material shift in how displaced Salvadorans think of ourselves, our relationality, and our localized responsibility. The mural is not simply a recreation of El Parque Libertad; it is collective, present, and localized meaning-making. For the generational diaspora who have not had the opportunity to visit the version of the park in El Salvador, this mural offers a gathering site in its own right.

There is something missing when the act of “visiting” the mural, standing next to it, spending time with it, allowing it to slowly reveal its details to you as you breathe, observe the texture, and even struggle to read the text through the fading paint is no longer possible. The mural derives meaning from its cultural and urban landscape, even as this landscape changes. Murals are not just static images on a wall; they are ongoing social practices.46 Murals not only have the power to reveal memories but are also sites of memory-making themselves. The City of Melbourne has offered to take a professional photograph of the work; however, the council states that the intellectual property of the images will be with the council-assigned photographer and the City of Melbourne.47

I thought about this as I showed my father the image of the mural on my 5.8-inch phone screen, as he attempted to zoom in on the photo’s detail as much as possible and look through his thick reading glasses. As we were housed at the Enterprise Hostel in Springvale—in southeastern Melbourne—my father had never seen the mural in person, and with the pandemic ongoing, he will probably not be able to visit before its demolition. Yet we, like others, were part of the mural even before we knew it existed. We might be scattered—locally and globally—yet we know through the embodied historical memory that community is not simply a postcode. In acknowledging the mural as social practice, we acknowledge not just that they are “urban form[s] of social expression”48 but that they are sites that hold the power to actively “shape discursive publics” and open up “other possible ways of being and imagining urban life.”49 As director of the Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project Lucha Martinez de Luna notes, “murals function as our historical textbooks.”50 She notes particularly the lack of representation in mainstream forms of education and literature. This is all the more important due to the exclusion of Central America even within Latin American discourse. Murals make visible what institutionalized memory practices refuse. Murals, as community-engaged practices, reflect a collective memoria histórica, asserting certain futures through community agency. They offer public pedagogy and “public pedagogy is always spatial.”51 To demolish the mural is to construct an absence in space but also in time, in the city but also in imagination, in the present but also in the past and future.

“The logic of neoliberal capital is notably keen on representing the present as a detachment or departure from the past; rarely a continuum,” writes Rasha Salti.52 This logic extends to understandings and treatments of displaced peoples. The experience of displacement, however, is not temporary; it is part of a continuum and is ongoing daily. The very existence of the Salvadoran community as uninvited guests on unceded lands is a continuous present. In 2020 the criminal trials began for the 1989 Jesuit Massacre at the Central American University (UCA) by US-trained death squads.53 The canonization of Archbishop Óscar Romero occurred forty-one years after his assassination, in 2018. There has yet to be a trial for the El Mozote massacre. My parents weren’t able to return to El Salvador until twenty-one years after having to leave. I returned for the first time only eight years ago. We are not talking about some distant, abstract past that is captured statically by a mural painted in 1990; we are talking about ever-unfolding presences. The mural’s destruction is one of many examples symptomatic of deep ongoing colonial wounds in so-called Australia and continues a politics of erasure. Roque Dalton, in his poetic homage to Salvadorans, writes that we are “los eternos indocumentados/the eternally undocumented,” referring to the global, historical undocumentedness of Salvadorans in exile. Perhaps this has also come to refer not just to papeles but to sites such as this mural.

When bringing this to light I am thanked (by the council) for highlighting the issue and am “invited” to provide a sentence “about migratory heritage that can be considered by the Art and Heritage Collection Panel at their next meeting,” to be considered and potentially included in the website.54 Rather than write a sentence for the City of Melbourne, I wrote this article.

Since the writing of the piece, the council confirmed a photograph of the mural will be hung in the foyer area of the new complex with a plaque. I recall, again, Ball’s quote about white remembrance finding its manifestation in plaques. The mural revealed something new every time I had an opportunity to visit. It instigated lessons, connections, and reconnections within a healing postwar displaced community. This is not just the demolishing of a wall but an emplaced engagement and future assemblages; an entire site flattened to a singular photograph and a plaque directing us to read what we already know in our bodies.

We remember, not because the mural will be destroyed but in spite of this.

Footnotes

While the mural is completely inaccessible, as of writing it has not been destroyed. The council has yet to provide me with a specific demolition date, although they had originally aimed to complete demolition by the end of 2021. “Closure date,” Participate Melbourne, link. ↩

The new “world-class” facility will have open floorplans, large windows, three multipurpose courts, an eight-lane pool, a new café, and so on. “Kensington Community Recreation Centre Redevelopment,” City of Melbourne, link. ↩

This, however, does not account for earlier Indigenous-led resistance. ↩

The church was a key site for workers, unions, students, and the political left. In the 1979 massacre, protesters found refuge in the church. The dent of the bullet caps can still be seen on the outside of the church where the military opened fire on them. There are twenty-one bodies buried in the church, including from these initial uprisings. See Jessica Orellana, “Conoce la historia de los 21 cuerpos enterrados en la iglesia El Rosario,” elsalvador.com, May 22, 2021, link. ↩

Email message to author on July 23, 2021. ↩

City of Melbourne council staff, phone conversation with author, July 22, 2021. ↩

Beatriz Santos, “From El Salvador to Australia: A Twentieth-Century Exodus to a Promised Land” (PhD diss., Australian Catholic University, 2006). ↩

According to the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Salvadorian community in Australia is now around 20,000. According to the 2016 census, Australians born in El Salvador totaled 9,500, with those of Salvadorian decent (born in Australia) totaling 8,700. What this suggests, therefore, is that the Salvadorian experience in Australia is a refugee experience. In the 2016 census there were 3,112 persons identified with Salvadoran ancestry with over half born in El Salvador. ↩

Tracy Ireland, Steve Brown, and John Schofield, “Situating (In)significance,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 26, no. 9 (April 2020): 826. ↩

Ireland et al., “Situating (In)significance,” 827. ↩

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409. ↩

Anita Heiss, “Our Truths: Aboriginal Writers and the Stolen Generations,” The BlackWords Essays (St. Lucia, Qld: AustLit, 2015), link. ↩

Paul Daily, “Why Does the Australian War Memorial Ignore the Frontier War?” The Guardian, September 12, 2013, link. ↩

See Lorena Allam, “‘Beyond Heartbreaking’: 500 Indigenous Deaths in Custody since 1991 Royal Commission,” The Guardian, December 5, 2021, link; and Amy McQuire, “In Canada and Australia, Aboriginal Women Reporting Disappearances Meet Entrenched Police Racism,” March 25, 2016, link. ↩

This occurred during one of Melbourne’s six hard lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, making it impossible for people to mobilize at the site due to ongoing restrictions. ↩

Chelsea Watego, Another Day in the Colony (St. Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2021), link. ↩

Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), xi–xxiv. ↩

Jade Macmillan, “Endeavour Replica to Sail around Australia to Mark 250 Years since Captain Cook’s Arrival,” The Guardian, January 22, 2019, link. ↩

Nakari Thorpe, “Government to Crack Down on Vandalism to Captain Cook Statues,” NITV, September 12, 2017, link. ↩

The white Australia policy (Immigration Restriction Act 1901) was an immigration policy that restricted racially discriminated against non-white, non-Europeans from entering the country in order to enforce a national white Australian identity post Federation. The UK Assisted Passage Migration Scheme (1945) was part of what came to be known as the “populate or perish” policy or the ten-pound-pom scheme that sought to attract British migration by offering free boat passage, with the intention to increase the population of Australia and build a white Australian colony. “It was a significant factor in increasing the European population in Australia,” link. ↩

Timmah Ball, “Imagining a Black, Queer Aboriginal Melbourne,” Literary Hub, December 12, 2018, link. ↩

Ruth De Souza, Danny Butt, Tania Cañas, and Genevieve Grieves, “Performing Statelessness: Creative Conversations between First Peoples and Refugees” in “Decolonisation and Performance Studies,” special issue, Global Performance Studies 5, no.1 (September 2022). ↩

Santos, “From El Salvador to Australia.” ↩

Many of these sites no longer exist as migrant hostels as policies have changed. They are now empty or, in the case of Springvale, fancy retirement homes. ↩

Kate Shaw, Peter Raisbeck, Chris Chaplin, and Kath Hulse, “Evaluation of the Kensington Redevelopment and Place Management Models Final Report,” University of Melbourne Faculty of Architecture Building and Planning, January 2013, 88, link. ↩

City of Melbourne council staff, phone conversation with author, July 22, 2021. ↩

Luke Enrique-Gomes, “Melbourne Parents Fight to Keep Bilingual Vietnamese Program at Footscray Primary School,” October 4, 2020, The Guardian, link. This advocacy was organized in part by ViệtSpeak—a community based, nonprofit advocacy organization based in Footscray. “ViệtSpeak, link. ↩

Ireland et al., “Situating (In)significance,” 833. ↩

Ireland et al., “Situating (In)significance,” 833. ↩

“About Us,” Heritage Victoria, link. ↩

“Heritage Act 2017,” Victorian Legislation, link. ↩

Heritage Victoria, email message with author, July 27, 2021. ↩

“Commonwealth Games Aquatic Sculptures-Eels 2006,” City Collection, City of Melbourne, link. ↩

“Collection Information” City of Melbourne, link. ↩

Rasha Salti, “A Short Glossary of the Present,” in Former West: Art and the Contemporary After 1989, ed. Maria Hlavajova and Simon Sheikh (London: MIT Press, 2016), 98. ↩

Tony Birch, “Shrine of Remembrance,” in The Politics of Public Space: Volume 3 (Melbourne: OFFICE, 2020). ↩

Deakin’s quote continues: “The Aboriginal race has died out in the South and is dying fast in the North and West even where most gently treated. Other races are to be excluded by legislation if they are tinted to any degree. The yellow, the brown, and the copper-coloured are to be forbidden to land anywhere.” Quoted in Christopher Mayers, “White Medicine, White Ethics: On the Historical Formation of Racism in Australian Healthcare,” Journal of Australian Studies 44, no. 3 (2020): 291. ↩

For more on the mosaic mural, see link. ↩

See Board 2 of the Lynch Bridge Project, “The Story of Newmarket Saleyards,” Melbourne’s Living Museum of the West, link. ↩

Email message to author, August 9, 2021. ↩

Cathay Smith, “Community Rights to Public Art,” St. John’s Law Review 90, no. 2 (July 2016): 385. ↩

Anne Parlane, “Keith Haring Mural Collingwood,” MEMO Review, June 19, 2021, link. ↩

“Restoration,” Culture Victoria, link. ↩

“Hosier Lane,” Visit Victoria, link. ↩

Ireland et al., “Situating (In)significance,” 832. ↩

Sang Weon Bae, “Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices” (M.A. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2016), 3. ↩

Head of Creative Urban Places, Creative City, email correspondence with author, August 3, 2021. See also Sang Weon Bae, “Balancing Past and Present: Reevaluating Community Murals and Existing Practices,” (M.A. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2016). ↩

Bae, “Balancing Past and Present,” 2. ↩

Zayd Minty, Laura Nkula-Wenz, Naomi Roux, Vaughn Sadie, Anna Selmeczi, and Rike Sitas, “Doual’Art: Art, Publics and the City as a ‘Field of Experience,’” in Perspectives from a Changing World, ed. Carin Kuoni, Jordi Balta Portoles, Nora N. Khan, and Serubiri Moses (Amsterdam: Valiz Books, 2020), 305. ↩

Oscar Perry Abello, “Denver May Soon Create the Country’s First Historic District Honoring the Chicano Movement,” Next City, July 16, 2021, link. ↩

Hannum Kathryn and Rhodes M, “Public Art as Public Pedagogy: Memorial Landscapes of the Cambodian Genocide,” Journal of Cultural Geograph 35, no. 3 (February 2018): 335. ↩

Salti, “A Short Glossary of the Present,” 97. ↩

Sam Jones, “Ex-Salvadoran Colonel Jailed for 1989 Murder of Spanish Jesuits,” The Guardian, September 11, 2020, link. ↩

Head of Creative Urban Places, Creative City, email correspondence with author, August 3, 2021. ↩

Dr. Tania Cañas is an artist-researcher based on unceded Kulin Territory. Her work looks at socially engaged and community-led creative practices as sites of collaboration, modalities of resistance, as well as ways to rethink processes and recast institutions.